All Good Things Must Come to an End: Kimble v Marvel

Kimble v. Marvel Entertainment, LLC, 135 S. Ct. 2401 (2015).

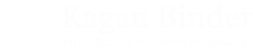

Kimble evaluates whether a patent owner can collect any kind of patent royalty (e.g., royalty under a license or royalty for an assignment) for activity occurring after a patent expires. The question puts Brulotte v. Thys Co., 379 U.S. 29 (1964) on trial. Brulotte ruled that a patent owner cannot collect license royalties for activity occurring after a licensed patent expires. Has the world changed so much in the past 55 years that Brulotte should now be overruled? Should parties be able to enter a mutually desirable deal where one party willingly agrees to pay patent royalties for activity occurring after a patent expires?

Kimble invented and patented (1990) a Spiderman toy that mimics how Spiderman shoots webs from his hands. Kimble approached Marvel to see if they would do a deal with him. Marvel initially declined, instead introducing its own web mimic toy. Kimble sued Marvel for patent infringement in 1997. The parties settled the patent dispute under a settlement deal where Marvel bought the asserted patent. Marvel paid Kimble an initial fee of just over $500,000 and agreed to pay a 3% royalty. The agreement never set an end date on the royalty obligation, appearing to set up a scheme under which Marvel would pay the patent royalty as long as Marvel sold the product.

Kimble invented and patented (1990) a Spiderman toy that mimics how Spiderman shoots webs from his hands. Kimble approached Marvel to see if they would do a deal with him. Marvel initially declined, instead introducing its own web mimic toy. Kimble sued Marvel for patent infringement in 1997. The parties settled the patent dispute under a settlement deal where Marvel bought the asserted patent. Marvel paid Kimble an initial fee of just over $500,000 and agreed to pay a 3% royalty. The agreement never set an end date on the royalty obligation, appearing to set up a scheme under which Marvel would pay the patent royalty as long as Marvel sold the product.

Neither Kimble nor Marvel was aware of the Brulotte doctrine when they placed their settlement agreement. Marvel discovered the doctrine circa 2006 and promptly brought a declaratory judgment action in federal district court to confirm that its royalty obligations would end in 2010 when the patent expired. The district court granted Marvel the declaratory relief it requested, and Kimble appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of appeals. The Ninth Circuit expressly announced disdain for the Brulotte doctrine but felt compelled to follow it. The appellate court affirmed that Marvel could stop paying royalty in 2010.

Kimble next appealed to the Supreme Court, requesting that Brulotte should be overruled. In practical effect, Kimble wanted Supreme Court permission to charge Marvel a royalty forever on the Spiderman toy.

The Supreme Court upheld Brulotte, ruling that a patent owner may not collect any royalty for any post-expiration activity. It did not matter to the Court whether the royalty was based on a patent license or a patent assignment. This meant that Marvel could stop paying patent royalty to Kimble in 2010. Justice Kagan, no relation by the way, wrote the decision for the Court.

The key to the Kimble decision is the fundamental principle underlying U.S. patent law. In exchange for describing and enabling an invention in a patent, the patent owner gets exclusivity to the invention for the patent term. But part of the bargain is that the invention passes to the public when the patent expires or is found to be invalid or unenforceable. The Court indicated that it carefully guards this bargain.

The Court further explained that its new decision here, and the original Brulotte doctrine, only limit the ability of a patent owner to collect patent royalty for post-expiration activity. Parties, according to the court, have legitimate ways to work around the Brulotte rule. As one example, license parties could agree that only activity that occurs during the patent term is subject to royalty, but a licensee can still be obligated to submit payment for that activity after the patent term expires. In other words, payments can occur at any time, pre- or post-expiration, so long as only activity inside the term is subject to royalty. The Court also noted that non-patent royalties are allowed without being tied to a patent term. An example includes a trade secret or know how royalty, either of which can go on indefinitely. Although the court did not cite a case example for such trade secret or know how royalties, these are within the doctrine of Aronson v. Quick Point Pencil Co., 440 U.S. 257 (1979) and it's more recent case law progeny.

In upholding Brulotte, the Court devoted many passages to the sanctity of stare decisis. The court explained that Supreme Court cases should not be overruled too easily and that Kimble failed to provide important enough reasons to set stare decisis aside. The Court observed that Congress has not overruled Brulotte by statute notwithstanding multiple opportunities to do so over the years as Congress continually reworked the patent laws. The Court believed that the hands off treatment by Congress is another factor that supported leaving the Brulotte decision in place. The Court also observed that the statutory and doctrinal underpinnings of Brulotte have stood the test of time.

In upholding Brulotte, the Court devoted many passages to the sanctity of stare decisis. The court explained that Supreme Court cases should not be overruled too easily and that Kimble failed to provide important enough reasons to set stare decisis aside. The Court observed that Congress has not overruled Brulotte by statute notwithstanding multiple opportunities to do so over the years as Congress continually reworked the patent laws. The Court believed that the hands off treatment by Congress is another factor that supported leaving the Brulotte decision in place. The Court also observed that the statutory and doctrinal underpinnings of Brulotte have stood the test of time.

Kimble tried to argue that the Brulotte test is unworkable as another basis to avoid stare decisis, but the Court disagreed. Justice Kagan wrote that Brulotte creates a bright line test that is easy to use in contrast to the totality of circumstances standard proposed by Kimble.

Kimble tried two more arguments to knock Brulotte down. First, Kimble argued that Brulotte is anticompetitive. Justice Kagan rejected this argument. Justice Kagan wrote that Brulotte was not based on anticompetitive principles, but rather on the fundamental patent law principle that patented subject matter must enter the public domain when the patent term expires. At its core, in other words, Brulotte is a patent case, not an antitrust case.

Second, Kimble and many amici argued that Brulotte stifles innovation. Justice Kagan rejected this argument as well. Kimble and many amici supporting Kimble failed to present any empirical evidence of this stifling effect.

Kimble and Brulotte are important cases. Royalty payments are a crucial aspect of technology deals, and these two cases set an important limitation on patent royalty strategies. The lesson for patent owners is to capture what you can during the patent term and to use other revenue harvesting strategies outside the term.

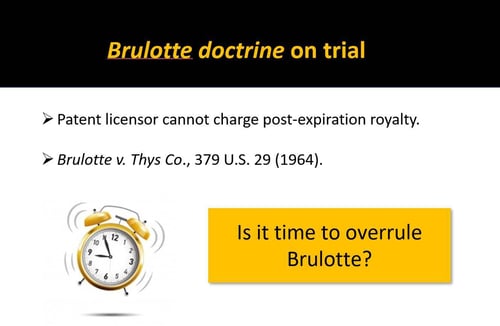

Did Kimble miss a crucial argument that could have protected his royalty stream? Recall that Kimble and Marvel agreed to their royalty scheme in a settlement agreement for a patent infringement suit. Might the Kimble royalty clause be enforceable due to its presence in a

settlement agreement? Kimble failed to present any argument that would balance policies of patent law with the judicial policy associated with settling disputes. Yet, judicial policy involving settlement agreements prevails over patent policy when these are at odds. Favoring judicial policy allows otherwise unenforceable clauses to be enforced if the clauses are in a settlement agreement.

For example, settlement policy prevailed over patent policy in Hemstreet v. Spiegel, Inc., 851 F.2d (Fed. Cir. 1988). To end an earlier patent infringement dispute, Hemstreet and Spiegel entered into a settlement agreement under which Spiegel contractually agreed to a “no challenge” clause. Pursuant to this no challenge clause, Spiegel agreed that it would not thereafter challenge patent validity. However, no challenge clauses generally are unenforceable under Lear v. Adkins, 89 S. Ct. 1902 (1969). The Lear Court ruled that licenses cannot block a licensee from challenging patent validity in view of the strong patent policy that unpatentable or invalid subject matter should be in the public domain.

In the subsequent 1988 dispute between Hemstreet and Spiegel, Spiegel pointed to the Lear policy, arguing that Spiegel must be allowed to challenge patent validity notwithstanding the no challenge clause in the earlier settlement agreement. Hemstreet countered that the strong judicial interest in settling disputes prevails over the Lear patent policy, making the no challenge clause enforceable in the context of a settlement agreement.

The Federal Circuit agreed with Hemstreet. In a competition between patent policy and judicial policy, judicial policy wins. Therefore, as an exception to Lear, a no challenge clause in a settlement agreement is binding and enforceable. Subsequent cases fairly consistently follow this ruling unless the no challenge clause in the settlement agreement is ambiguous or too narrow. See e.g., Flex-Foot, Inc. v. CRP, Inc., 57 USPQ2d 1635 (Fed. Cir. 2001)(enforceable no challenge clause in settlement agreement); Foster v. Hallco Mfg. Co., Inc., 20 USPQ2d 1241 (Fed. Cir. 1991) (enforceable no challenge clause in settlement agreement); Compare Baseload Energy Inc. v. Roberts, 96 USPQ2d 1521 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (no challenge clause in settlement agreement not enforceable); Ecolab, Inc. v. Paraclipse, Inc., 62 USPQ2d 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (no challenge clause in settlement agreement not enforceable); Diversey Lever, Inc. v. Ecolab, Inc., 52 USPQ2d 1062 (Fed. Cir. 1999) (no challenge clause in settlement agreement not enforceable); Howmedica Osteonics Corp. v. Wright Medical Technology, Inc., 88 USPQ2d 1129 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (no challenge clause in settlement agreement not enforceable).

Like the agreement clause at issue in Hemstreet, the royalty clause at issue in Kimble also was in a settlement agreement. Did not Kimble have a similar argument that its royalty clause would be enforceable as a matter of judicial policy? The very same patent policy (patents should not usurp subject matter that belongs to the public) was at issue against the very same judicial policy (settlement commitments further the policy of expedient and orderly settlement of disputes to foster judicial economy), and so the same balance should have resulted. Would the Court have qualified its Kimble ruling if the patent owner had thought to apply the principles of Hemstreet?

What else could Kimble have done to protect its royalty stream? Kimble should have thought of a way to incorporate know-how grants into the original settlement agreement with Marvel.

Further, even without the benefit of hindsight, Kimble had plenty of time to fix his situation. Marvel brought its DJ action in 2006, which was about four years before the patent expired in 2010. Kimble could have worked on improving his toy product in a way in which updated patent or know-how rights could have been additionally licensed to Marvel or another interested licensee. The market had to be profitable or else Marvel would not have fought so hard for nine years to cancel its royalty obligation.

Licensors generally can benefit from working on technology improvements even if the twilight hour for royalties and patent term expiration is far off. In fact, licensors should start to think of improvements on the day the most current embodiment is finalized. This renewed development effort may even start before license discussions begin or are contemplated. Many companies use technology improvements to stay competitive. Some companies fail because they sit still.