Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft v. Sirius XM Radio Inc., No. 2018-2400 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 17, 2019).

This case presents many important lessons for sublicense strategies.

This case presents many important lessons for sublicense strategies.

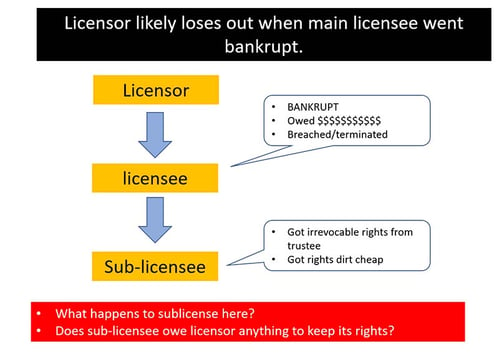

Fraunhofer exclusively licensed Worldspace under patent rights protecting technology to stream data via multiple data streams. The license was irrevocable and worldwide. Worldspace had the right to sublicense. Worldspace was obligated to pay a $1 million license fee in installments. Worldspace gave an irrevocable sub-license to Sirius XM.

Worldspace went bankrupt without having completed all of its installment payments. In bankruptcy, independent of the licensor Fraunhofer, the trustee and sublicensee Sirius XM reached a settlement under which Sirius XM paid licensee Worldspace a lump sum, with the result that Sirius XM kept its sublicense, now paid up as far as Worldspace and Sirius XM were concerned.

Worldspace and its bankruptcy trustee might have been happy, but not Fraunhofer. Fraunhofer sued Sirius on grounds that the Worldspace bankruptcy compromised the Sirius XM sublicense. Consequently, Sirius no longer had rights under the Fraunhofer patents. Basically, Fraunhofer was looking to Sirius XM to be made whole, or even more than whole based on the alleged damages, due to the impact of the Worldspace bankruptcy.

So many sublicense issues were raised, some guidance was given, but ultimately the Federal Circuit made no rulings. The Federal Circuit remanded the case to the lower court for further proceedings consistent with the guidance put on the table by the Federal Circuit.

So many sublicense issues were raised, some guidance was given, but ultimately the Federal Circuit made no rulings. The Federal Circuit remanded the case to the lower court for further proceedings consistent with the guidance put on the table by the Federal Circuit.

Many lessons are identified:

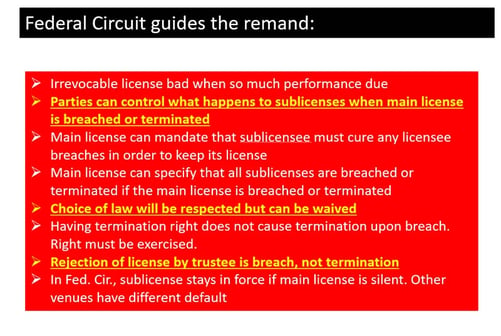

- It is a bad idea for a licensor to give an irrevocable license when licensee performance is so executory and substantial money is at risk. If an irrevocable license is to be granted, it should not be irrevocable until all material obligations, such as payment of all money owed, have been met.

- When a master license is breached or terminated, the parties can control the resultant impact on any sublicenses. The parties failed to address this in any way in their master license. The Federal Circuit had some polite words to identify this shortcoming, but reading between the lines it is clear that the Federal Circuit criticized Fraunhofer for its folly in failing to address this issue.

- The master agreement can provide that a sublicensee must cure any breaches by the sub-licensor or risk losing its sublicense.

- The master agreement can require sublicenses to provide performance to the main licensor of all obligations in the master license and sublicense in order to keep its sublicense.

A master agreement can specify that termination or breach of the master license causes any sublicense to be correspondingly terminated or breached.

A master agreement can specify that termination or breach of the master license causes any sublicense to be correspondingly terminated or breached.- A choice of law provision will be respected, but it can be waived. Here a choice of Swiss law was waived when the parties applied U.S. law all the way through the Federal Circuit proceedings and did not raise the possible application of Swiss law until getting to the Supreme Court.

- Having a termination right with respect to a triggering event does not mean the termination occurs when the event occurs. The right must be exercised.

- Rejection of a license in bankruptcy is a breach, not a termination.

- Bankruptcy of the licensee gives licensor a right of termination against the licensee.

- When a master license terminates, and the agreement is silent on the impact on sublicenses, different venues treat the impact on sublicenses differently. Some have held that the sublicenses terminate, too. The Federal Circuit states that sublicenses do not terminate by default upon master license termination when the master license is silent.