License Negotiations Breaking Down? You've Got Homework

Halo Electronics, Inc. v. Pulse Electronics, Inc., 136 S. Ct. 1923 (2016).

The Halo decision created a new regime that has made it easier for patent owners to get enhanced damages against accused infringers under 35 USC 284. The Halo decision directly impacts license practice in the event that license negotiations break down. If a licensee plans to walk away from license negotiations, Halo makes it crucial for the licensee to kick the tires of the rejected patent properties, so to speak, and then to document its analysis of noninfringement, invalidity, and/or unenforceability in a written opinion. Halo implies that the exiting licensee has an increased risk of paying enhanced damages as a willful infringer if the licensee fails to do its homework.

The Halo decision created a new regime that has made it easier for patent owners to get enhanced damages against accused infringers under 35 USC 284. The Halo decision directly impacts license practice in the event that license negotiations break down. If a licensee plans to walk away from license negotiations, Halo makes it crucial for the licensee to kick the tires of the rejected patent properties, so to speak, and then to document its analysis of noninfringement, invalidity, and/or unenforceability in a written opinion. Halo implies that the exiting licensee has an increased risk of paying enhanced damages as a willful infringer if the licensee fails to do its homework.

Section 35 USC 284 of the patent statute provides courts with discretion to award enhanced damages, with treble damages being the upper limit. Section 284 reads as follows (emphasis added):

35 U.S.C. 284 DAMAGES.

Upon finding for the claimant the court shall award the claimant damages adequate to compensate for the infringement but in no event less than a reasonable royalty for the use made of the invention by the infringer, together with interest and costs as fixed by the court.

When the damages are not found by a jury, the court shall assess them. In either event the court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed. Increased damages under this paragraph shall not apply to provisional rights under section 154(d).

The court may receive expert testimony as an aid to the determination of damages or of what royalty would be reasonable under the circumstances.

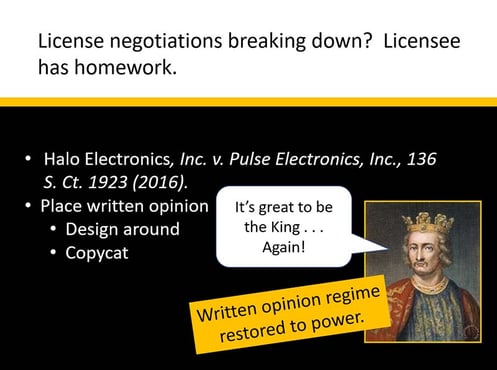

Although providing statutory authority for enhanced damages, the statute itself fails to instruct when enhanced damages should be awarded. The courts took on this responsibility and have developed standards for awarding enhanced damages in “egregious cases.” Enhanced damages have not been awarded in ordinary cases where bad behavior is absent. In essence, a party that acts egregiously, such as by willfully infringing a patent, risks having to pay up to treble damages when called to task.

Although providing statutory authority for enhanced damages, the statute itself fails to instruct when enhanced damages should be awarded. The courts took on this responsibility and have developed standards for awarding enhanced damages in “egregious cases.” Enhanced damages have not been awarded in ordinary cases where bad behavior is absent. In essence, a party that acts egregiously, such as by willfully infringing a patent, risks having to pay up to treble damages when called to task.

The modern era of patent law began with the creation of the Federal Circuit in 1982. Several milestones have occurred in the modern era that guide the award of enhanced damage awards under Section 284. Major milestones occurred in 1983, 2007, 2012, 2016, and then post-2016.

In 1983, the Federal Circuit established the standard that competent opinions regarding patent infringement, validity, enforceability, etc. could avoid willful infringement and the associated enhanced damages. The court announced this standard in Underwater Devices Inc. v.

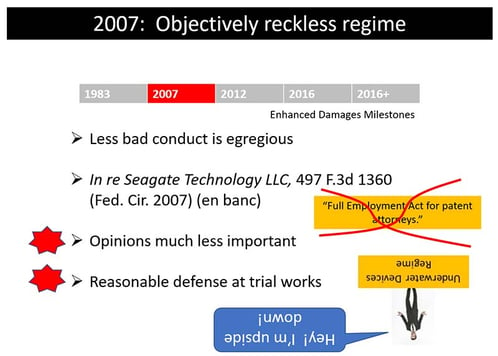

Morrison-Knudsen Co., 717 F.2d 1380 (Fed. Cir. 1983). In ensuing years, several nuances of the Underwater Devices standard evolved, creating traps and pitfalls for the unwary. Some principles remained generally clear, though. First, the opinion had to be obtained around the same time as the alleged willful infringement. Second, raising a defense at trial, even a rock solid one, could not avoid willful infringement if the proper homework was not done earlier at the right time. Commentators referred to Underwater Devices as a “full employment act” for patent attorneys, as the demand for written opinions soared.

Morrison-Knudsen Co., 717 F.2d 1380 (Fed. Cir. 1983). In ensuing years, several nuances of the Underwater Devices standard evolved, creating traps and pitfalls for the unwary. Some principles remained generally clear, though. First, the opinion had to be obtained around the same time as the alleged willful infringement. Second, raising a defense at trial, even a rock solid one, could not avoid willful infringement if the proper homework was not done earlier at the right time. Commentators referred to Underwater Devices as a “full employment act” for patent attorneys, as the demand for written opinions soared.

The willful infringement standards flipped in 2007, when the Federal Circuit decided In re Seagate Technology LLC, 497 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (en banc), cert. denied, 129 S. Ct. 1917 (Feb. 25, 2008). The Seagate decision set forth a new “objectively reckless” standard that made it much easier for accused infringers to avoid enhanced damages. In contrast to standards under Underwater Devices, written opinions at the time of the conduct at issue were much less important, although still beneficial from time to time. Also in contrast to standards under Underwater Devices, raising a reasonable defense for the first time at trial was good enough to avoid willful infringement.

The AIA was enacted in 2012, another milestone. The new statute section at 35 USC 298 appeared to make it even clearer that opinions were much less important in the Seagate regime. Section 298 reads as follows (emphasis added):

35 U.S.C. 298. ADVICE OF COUNSEL

The failure of an infringer to obtain the advice of counsel with respect to any allegedly infringed patent, or the failure of the infringer to present such advice to the court or jury, may not be used to prove that the accused infringer willfully infringed the patent or that the infringer intended to induce infringement of the patent.

The statute very clearly diminishes the role of opinions in any willful infringement analysis. Or does it?

Apparently the statute does not mean what it says. The Supreme Court gutted Section 298 when the Supreme Court issued its Halo decision in 2016, another milestone. The gutting effect is shown in the Halo aftermath, described below, where securing opinions at the time of the conduct at issue has become paramount again. The pendulum of the role of opinions has swung away from relative obscurity under the Seagate (2007) test back towards the opinion world of Underwater Devices (1983).

Apparently the statute does not mean what it says. The Supreme Court gutted Section 298 when the Supreme Court issued its Halo decision in 2016, another milestone. The gutting effect is shown in the Halo aftermath, described below, where securing opinions at the time of the conduct at issue has become paramount again. The pendulum of the role of opinions has swung away from relative obscurity under the Seagate (2007) test back towards the opinion world of Underwater Devices (1983).

Halo actually involved two disputes: Halo Electronics, Inc. v. Pulse Electronics, Inc. (electronics) and Stryker Corp. v. Zimmer, Inc. (orthopedics). Of the two, Halo v. Pulse related to a license dispute. Halo suggested that Pulse take a license, but Pulse declined. Pulse had an opinion from an engineer that the Pulse product did not infringe the Halo patent claims. After Pulse exited the license negotiations without taking a license, Halo sued Pulse for patent infringement, also alleging willful infringement. Stryker v. Zimmer followed a different path, as a license was not involved, Ultimately, both cases ended up in the Supreme Court, where the standard for evaluating enhanced damages under Section 284 was at issue.

The Supreme Court agreed with prior rulings under the Seagate regime that willful infringement and enhanced damages should only target egregious conduct. But, the Supreme Court felt the Seagate test was too rigid and allowed bad actors to avoid willful infringement too easily. Per the Supreme Court, the Seagate test ignored bad conduct when it occurred, allowing bad actors to escape via reasonable defenses raised at trial. The Supreme Court instructed that bad conduct must be judged when it occurs and should not correlate to whether good defenses are raised later at trial. The Supreme Court then gutted Section 298 with a somewhat circular argument as to why opinions are still important. Both disputes at issue in Halo were remanded for adjudication under the revised principles.

After shredding Seagate and gutting Section 298, what willful infringement test did the Supreme Court put on the table? None. It was left to lower courts in the Halo aftermath to fashion standards compatible with the Supreme Court decision.

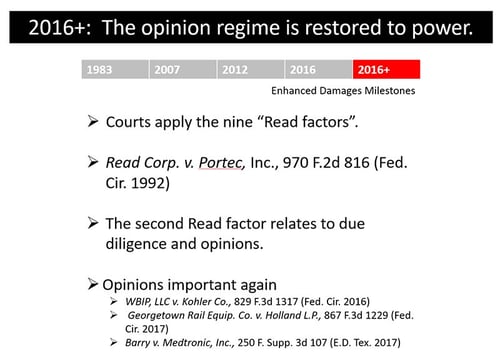

The Halo aftermath shows that opinions once again are crucial to avoid enhanced damages for egregious conduct such as willful infringement. District Courts and the Federal Circuit currently evaluate willful infringement in the context of the nine “Read factors” per Read Corp. v. Portec, Inc., 970 F.2d 816 (Fed. Cir. 1992). Among the nine factors, the second factor turns on whether the accused infringer did any due diligence or obtained an opinion. The failure to obtain opinions were significant factors leading to willful infringement and enhanced damages in WBIP, LLC v. Kohler Co., 829 F.3d 1317 (Fed. Cir. 2016); Georgetown Rail Equip. Co. v. Holland L.P., 867 F.3d 1229 (Fed. Cir. 2017); and Barry v. Medtronic, Inc., 250 F. Supp. 3d 107 (E.D. Tex. 2017).

The Halo decision and its aftermath provide important licenses for potential licensees who want to exit license negotiations. If a potential licensee intends to exit negotiations while remaining in the market with a competitive product, the potential licensee must do its homework to avoid willful infringement and enhanced damages. The party should do due diligence to evaluate noninfringement, invalidity, and/or unenforceability of the rejected patents. Timing is important, as the evaluation should occur at the time of the conduct in question. A written opinion should document the evaluation. While some cases allow non-attorneys to render opinions, counsel is best positioned to render these opinions. The opinion needs to be properly communicated and properly relied upon. The process should be carried out with strategies to protect attorney client communications and attorney work product at all stages.