Patentees who sell equipment and associated consumables are vulnerable to the exhaustion doctrine

A common business model occurs when patentee sells or even gives away patented equipment to pave the way for lucrative sales of proprietary consumables used in the equipment. Often, patentee intends to make most of its revenues from sales of the proprietary consumables. Are patent rights useful to support this model?

A common business model occurs when patentee sells or even gives away patented equipment to pave the way for lucrative sales of proprietary consumables used in the equipment. Often, patentee intends to make most of its revenues from sales of the proprietary consumables. Are patent rights useful to support this model?

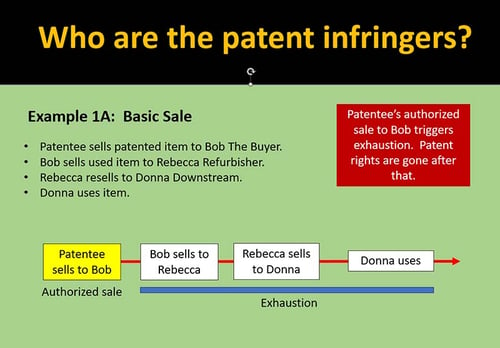

The ability of patent rights to protect the market for proprietary consumables was at issue in the fall of 2013. Patent rights did not fare so well as a result of patent exhaustion. Two Federal Circuit cases at that time held that sales of equipment exhausted patent rights associated with the equipment and its use. This allowed third parties to sell proprietary consumables used in the equipment without risk of patent infringement. See Keurig, Inc. v. Sturm Foods, Inc., 108 USPQ 1648 (Fed. Cir. 2013) and Lifescan Scotland, Ltd. v. Shasta Technologies, LLC, 108 USPQ2d 1757 (Fed. Cir. 2013).

After Keurig and Lifescan, it appeared as if third parties could readily invade the market with discounted consumables and grab market share without risk of patent infringement. Keurig and Lifescan appeared to have weakened patent rights considerably.

Patent owners can take heart that two further Federal Circuit decisions limit the reach of the Keurig and Lifescan cases. These two cases indicate that patent rights might still have some vulnerabilities in the task of protecting proprietary consumables but nonetheless are more effective to protect the patentee than was at first indicated by Keurig or Lifescan. The two cases are Helferich Patent Licensing, LLC v. The New York Times Co., 778 F.3d 1293 (Fed. Cir. 2015) and then a few years later Auto. Body Parts Ass'n v. Ford Glob. Techs., LLC , 2018-1613 (Fed. Cir. Jul. 23, 2019).

Patent owners can take heart that two further Federal Circuit decisions limit the reach of the Keurig and Lifescan cases. These two cases indicate that patent rights might still have some vulnerabilities in the task of protecting proprietary consumables but nonetheless are more effective to protect the patentee than was at first indicated by Keurig or Lifescan. The two cases are Helferich Patent Licensing, LLC v. The New York Times Co., 778 F.3d 1293 (Fed. Cir. 2015) and then a few years later Auto. Body Parts Ass'n v. Ford Glob. Techs., LLC , 2018-1613 (Fed. Cir. Jul. 23, 2019).

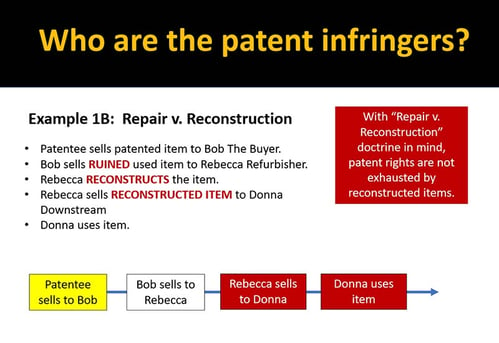

The Ford case has the simpler fact pattern and is a better starting point to evaluate the situation. Ford sells pickup trucks for which the hood is protected by design patent rights. When a third party sold replacement hoods, Ford sued the third party for design patent infringement. Importantly, as will be explained below with respect to the Helferich case, it is important that Ford sued the hood supplier for its own direct infringement as opposed to indirect infringement of patent rights used by Ford truck owners.

The third party defended based on exhaustion. The third party relied on both Keurig and Lifescan in its brief to argue that Ford’s sale of the truck exhausted all its patent rights in the vehicle, allowing third party replacement parts to be sold without a risk of patent infringement.

The third party defended based on exhaustion. The third party relied on both Keurig and Lifescan in its brief to argue that Ford’s sale of the truck exhausted all its patent rights in the vehicle, allowing third party replacement parts to be sold without a risk of patent infringement.

The Federal Circuit rejected the defense and held that the third party infringed. The Federal Circuit reasoned that exhaustion only applies to something sold by the patentee. The accused infringer, not patentee, sold the replacement hoods at issue. Note that this reasoning does not gel with the opposite results reached in Keurig or Lifescan, as the beverage pods and test strips in those earlier cases were not sold by the patentee either, yet exhaustion still applied. More is going on, which will be become more clear when the Helferich case is discussed below. The good news for patent owners is that Ford makes clear that patent rights remain viable to protect the market for patented replacement parts.

Although the accused infringer in Ford relied on Keurig and Lifescan, the court in Ford made no mention of Keurig or Lifescan in its decision. Not to reconcile them with its holding or even to distinguish them. Further, to reject the exhaustion defense, the Federal Circuit in Ford relied on an 1865 case from state court in New Hampshire where sales of a sewing machine did not exhaust patent rights for the patented consumable supplies used in the sewing machines.

Although the accused infringer in Ford relied on Keurig and Lifescan, the court in Ford made no mention of Keurig or Lifescan in its decision. Not to reconcile them with its holding or even to distinguish them. Further, to reject the exhaustion defense, the Federal Circuit in Ford relied on an 1865 case from state court in New Hampshire where sales of a sewing machine did not exhaust patent rights for the patented consumable supplies used in the sewing machines.

Did the Ford decision quietly overrule Keurig and Lifescan through purposeful disregard?

Perhaps not. More likely, Keurig and Lifescan are more limited in scope than was at first perceived when the two decisions emerged in 2013. The more complicated Helferich case from 2015 shows how to reconcile the situation.

In Helferich, the patent owner owned two related patent portfolios. A first portfolio protected mobile handsets. The decision reports that every handset sold in the United States is licensed under these handset patents. It was undisputed that handset users practiced the handset patent rights.

The second portfolio of patents protected content that could be used by the handset users. Content providers practiced the content patents, but there was no evidence that the handset users practiced any of the content patent rights.

The second portfolio of patents protected content that could be used by the handset users. Content providers practiced the content patents, but there was no evidence that the handset users practiced any of the content patent rights.

Some content providers were licensed. Some were not. Patentee sued an unauthorized content provider for infringement of the content patent rights. Quite significantly as it would turn out, patentee sued the unauthorized content provider for its own direct infringement of the content patent rights, not for indirect infringement of the handset patent rights used by the authorized handset buyers.

That last sentence is so important, it is worth reading again. This is the foundation for the court’s holding and the key to reconcile Helferich and Ford with Keurig and Lifescan.

The accused infringer in Helferich relied on an exhaustion defense. The accused infringer defended that the exhaustion of the handset patent rights by the authorized handset users (which was all handset users in the United States as a practical matter) allowed the accused infringer to supply the handset users with content under the separate but related content patents. According to the accused infringer, this directly followed from Keurig and Lifescan.

Keep in mind that Helferich was decided in 2015, four years earlier than the 2019 Ford decision discussed above. Although Ford trivialized Keurig and Lifescan in 2019, the reliance on Keurig and Lifescan seemed pretty sound in 2015. To the extent that content can be viewed as a proprietary consumable with respect to handsets, reliance upon Keurig and Lifescan as authority to trigger exhaustion was reasonable.

Keep in mind that Helferich was decided in 2015, four years earlier than the 2019 Ford decision discussed above. Although Ford trivialized Keurig and Lifescan in 2019, the reliance on Keurig and Lifescan seemed pretty sound in 2015. To the extent that content can be viewed as a proprietary consumable with respect to handsets, reliance upon Keurig and Lifescan as authority to trigger exhaustion was reasonable.

Even though the exhaustion defense appeared to be solidly grounded, the Federal Circuit rejected the exhaustion defense. The court explained that exhaustion is not applied unless “the patentee’s allegations of infringement, whether direct or indirect, entail infringement of the asserted claims by the authorized acquirers either because they are parties accused of infringement or because they are the ones allegedly committing the direct infringement[.]” The court further explained that exhaustion is available as a defense “only when the patentee’s assertion of infringement was, or depended on, an assertion that an authorized acquirer was using the same invention by infringing the asserted claims.”

In short, exhaustion is only available as a defense if asserted claims are exhausted, and only claims practiced by an authorized user can be exhausted. The Federal Circuit pointed out that the direct infringement claim was based on practice of the content patent rights, but there was no evidence submitted that the authorized handset purchasers practiced any content patent claims. Even though the authorized handset acquirers’ practice of the related handset claims might have exhausted those handset claims, those were not asserted against the accused content provider. The Federal Circuit emphasized that exhaustion does not transfer to related, but separate content patents never practiced by those users.

Applying these principles, the content provider infringed. The asserted content claims were not exhausted because there was no showing that the authorized handset acquirers practiced the asserted content claims.

The court even helped sort out potential inconsistencies and potential confusion among its recent decisions by explaining why Keurig and Lifescan could be distinguished. In Lifescan, the accused infringer supplied test strips used in blood glucose meters. Patent owner asserted

indirect infringement of claims that were practiced and exhausted by authorized acquirers of the glucose meters. Hence, in contrast to the Helferich situation, the asserted claims in Lifescan were exhausted by authorized acquirers. In Keurig, the accused infringer sold pods used in patented brewers. Patent owner asserted indirect infringement of method claims that were practiced and exhausted by the authorized acquirers of the brewers.

Helferich helps to understand how the two pairs of cases (Keurig and Lifescan, on the one hand, and Helferich and Ford on the other) are reconciled. In Keurig and Lifescan, authorized acquirers exhausted the asserted claims. There was no direct infringement and hence no indirect infringement. In Helferich and Ford, in contrast, there were no authorized acquirers to exhaust the asserted claims, and direct infringement was asserted.

Perhaps if patentee in Helferich had asserted indirect infringement of handset claims, the accused infringer could have escaped using the exhaustion defense. The lesson for patentee is to assert direct infringement when you can and think twice before asserting indirect infringement of claims practiced by authorized buyers. Another lesson of Helferich is that a direct infringer cannot just piggy back onto another’s license on whim in order to escape direct infringement. Also, it remains possible that Keurig and Lifescan retain vitality for the point that it would be possible for an indirect infringer to piggy back onto another’s license if that other license negates the direct infringement on which the indirect infringement is based.

This line of Federal Circuit cases highlight considerations for both patentee and third party suppliers in markets in which revenue is derived from the supply of consumables. Patentee should make sure that its inventory of claims guard against both direct users of its equipment and consumables as well as claims that are practiced only by third party suppliers of the consumables. The risk is that any claims practiced by the authorized acquirers will be exhausted. In the meantime, parties looking to get into the market with competitive consumables should make sure that defenses other than exhaustion are used to negate claims that cover the consumables but are not practiced by the authorized acquirers.