Pitfalls under the implied license doctrine

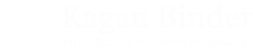

A myriad of law and fact circumstances create implied licenses. Scholars have commented that the law is a morass of doctrines that overlap and/or conflict.1 Nonetheless, a substantial majority of implied license cases fall into one or more of the following categories:

- Fixing an existing contract, such as filling in gaps, correcting mistakes, interpreting ambiguities.

- Conduct/actions, often in combination with words, establish an enforceable contract. (This category is very similar to oral contracts established by words alone. It’s not a big leap that words and conduct also can create an implied contract.)

- Preventing unjust enrichment, such as when a hired manufacturer is allowed to sell patented items to mitigate damages when the patent owner breaches its contract obligations and refuses to buy the manufactured items or such as when patent owners are allowed to earn reasonable rewards but not “private fortunes” or double recoveries.

- Protecting or implementing important patent policies that impact the public such as overbroad extension of patent rights to unpatented items, extending patent term, price fixing, restricting competitive development, etc.

The implied license cases discussed below fall into mainly the last two of these categories and are strongly influenced by equity. There may or may not be patent exhaustion principles at play as well. Often, the cases prevent a patent owner from asserting overbroad patent scope. In others, the cases trim back otherwise legitimate claim scope on principles that the patent owner has already been fairly compensated. Often, there is conduct by the patent owner that induces reliance by the party who at the time, or even much later with hindsight, asserts implied license. In Bandag, Inc. v. Al Bolser’s Tire Stores,2 a nascent Federal Circuit identified detrimental reliance as a key principle that is at play in many implied license cases:

The implied license cases discussed below fall into mainly the last two of these categories and are strongly influenced by equity. There may or may not be patent exhaustion principles at play as well. Often, the cases prevent a patent owner from asserting overbroad patent scope. In others, the cases trim back otherwise legitimate claim scope on principles that the patent owner has already been fairly compensated. Often, there is conduct by the patent owner that induces reliance by the party who at the time, or even much later with hindsight, asserts implied license. In Bandag, Inc. v. Al Bolser’s Tire Stores,2 a nascent Federal Circuit identified detrimental reliance as a key principle that is at play in many implied license cases:

[A]n implied license cannot arise out of the unilateral expectations or even reasonable hopes of one party. One must have been led to take action by the conduct of the other party.

Met-Coil Systems Corp. v. Korners Unlimited, Inc.,3 and Bandag, are early Federal Circuit cases addressing when authorized sales of patented items trigger implied licenses. These cases were decided in the early 1980s but remain good law. The principles of these two early cases were endorsed and expanded in the Anton/Bauer case seventeen years later. The Supreme Court’s Quanta decision from 2008 endorses the law set forth in these cases, too. Several recent cases apply the law in interesting ways. Met-Coil is an optimum place to begin discussion.

1. Met-Coil Systems Corp. v. Korners Unlimited, Inc.

Met-Coil and its affiliates (collectively Met-Coil) developed and commercialized a duct fabrication system. The product line included three main products that Met-Coil intended to sell to its customers:

- metal duct sections;

- roll forming equipment that shaped the ends of the duct sections, allowing the duct sections to be interconnected with other duct components; and

- “special” corners that were shaped to connect to the roll formed duct sections.

Met-Coil protected the equipment and a method of using the equipment to make ductwork from the equipment, duct sections, and corners. The corners themselves were unpatented.4

Met-Coil customers bought the equipment from Met-Coil; these sales were unrestricted, i.e., without sales terms or notices at the time of sale that imposed an obligation on the equipment customers to buy ducts or corners from Met-Coil. Thus, at the time of sale, the equipment customers had no contract obligation or even knowledge that Met-Coil might require them to buy ducts and corners from Met-Coil. Met-Coil did issue post-sale notices to this effect.

Met-Coil customers bought the equipment from Met-Coil; these sales were unrestricted, i.e., without sales terms or notices at the time of sale that imposed an obligation on the equipment customers to buy ducts or corners from Met-Coil. Thus, at the time of sale, the equipment customers had no contract obligation or even knowledge that Met-Coil might require them to buy ducts and corners from Met-Coil. Met-Coil did issue post-sale notices to this effect.

Importantly, the Met-Coil equipment had only one reasonable and intended use, namely to be used to roll form duct sections in the patented method.

Contrary to Met-Coil’s expectations, its equipment customers did not purchase its corners. The customers bought corner pieces from Korners Unlimited, presumably at lower prices.

Met-Coil believed that only customers who bought all three of the equipment, ducts, and corners from Met-Coil had authority to practice the patented method. Consequently, Met-Coil alleged that those customers who instead bought corners from Korners directly infringed the Met-Coil method claims. Met-Coil sued Korners for inducing and contributing to the direct infringement. Clearly, Met-Coil was not happy that Korners usurped Met-Coil’s expected revenue stream from corner sales.

Met-Coil believed that only customers who bought all three of the equipment, ducts, and corners from Met-Coil had authority to practice the patented method. Consequently, Met-Coil alleged that those customers who instead bought corners from Korners directly infringed the Met-Coil method claims. Met-Coil sued Korners for inducing and contributing to the direct infringement. Clearly, Met-Coil was not happy that Korners usurped Met-Coil’s expected revenue stream from corner sales.

Korners defended that purchasers of the equipment had an implied license to use that equipment to practice the patented method using the third party corners obtained from Korners.

Consequently, there was no direct infringement and, hence, no induced or contributory infringement.

The Federal Circuit affirmed summary judgment in favor of Korners on grounds that purchasers of the Met-Coil equipment enjoyed an implied license. As a consequence of the license, those equipment purchasers could buy unpatented corners from any third party. The decision clearly thwarted the business model and desiccated an intended revenue stream of the patent owner, Met-Coil.

In reaching its decision, the Federal Circuit relied on these factors:

- The equipment sale was unrestricted.

- The equipment had only one use, which was to practice the patented method.

- The facts “plainly indicated” that a license should be implied, because there was no contrary notice or contractual obligation at the time of sale. The post-sale notice issued by Met-Coil was ineffective to impact circumstances of the earlier sale itself.

- The corners were unpatented.

The Met-Coil analysis is circular: an implied license exists legally when an implied license exists factually. This is not much guidance. The rule begs the question as to when facts plainly indicate a license.

Not surprisingly, Met-Coil leaves open several questions:

- The meaning of “plainly indicate” is not set forth, so the boundaries of when facts are sufficient to plainly indicate something are uncharted territory.

- What happens if the process in question involves multiple stages so that additional patented equipment is required at those additional stage(s)? Does buying a single piece of equipment from the patent owner authorize the customer to buy additional equipment from someone else under the implied license theory even if the additional equipment is patented by the patent owner?

- If the special corners had been patented, would the result have been different? Could a customer buy special corners from Met-Coil but then buy equipment from a third party?

- If in fact Met-Coil had given notice to its customers at the time of sale, would that one fact have changed the outcome?

- What if the Met-Coil equipment had three uses, but all three were patented by Met-Coil and/or a third party? What if the Met-Coil equipment had two distinct uses, but the two uses are both physically and conceptually easy to separate?

2. Anton/Bauer Inc. v. PAG Ltd.5

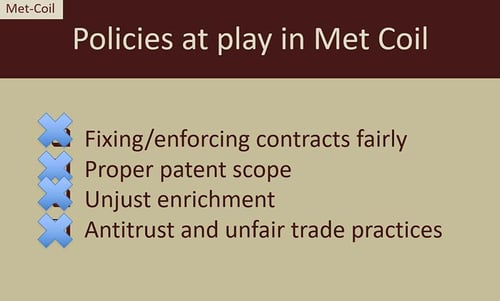

The Federal Circuit decided Met-Coil nearly 30 years ago, back in 1984. In 2003, the Federal Circuit endorsed Met-Coil and extended the reach of implied license law even further in Anton/Bauer.

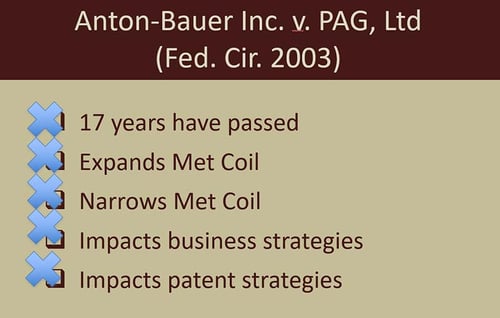

Anton/Bauer invented a battery connection system that is a combination of a male (M) and female (F) plates. The two plates can be connected mechanically and electrically. The plates are used to couple battery packs to cameras. The F plate is attached to a camera, while the M plate is integrated into a battery housing.

Anton/Bauer patented the combination of the M and F plates; the M and F plates individually were not patented. The F plate sold by Anton/Bauer had one and only one use, namely, to be used in combination with an M plate.

Anton/Bauer sold both F and M plates, but only separately. Anton/Bauer never sold the F and M plates together. Clearly, the Anton/Bauer business model contemplated that revenue would be generated from the individual sales of M and F plates.

PAG disrupted Anton/Bauer’s business model. PAG manufactured and sold M plates specifically designed to be used in combination with the F plates of Anton/Bauer. To the chagrin of Anton/Bauer, customers who bought F plates directly or indirectly from Anton/Bauer bought M plates from PAG,6 not Anton/Bauer. PAG customers thus practiced under the Anton/Bauer patent claims protecting the M-F combination while obtaining only F plates from the patent owner.

PAG thereby usurped M plate sales and the corresponding revenue from Anton/Bauer. Not happy at all about this, Anton/Bauer believed that only customers who bought both F and M plates from Anton/Bauer had authority to practice the patented combination. Consequently, Anton/Bauer alleged that PAG customers directly infringed the Anton/Bauer combination claims when a PAG M plate was combined with an Anton/Bauer F plates. Because PAG customers were the alleged direct infringers, Anton/Bauer sued PAG for inducing or contributing to the direct infringement.

PAG defended that Anton/Bauer’s F plate customers had an implied license to use a properly obtained F plate in combination with an unpatented M plate to practice the patented combination using PAG’s M plates. Consequently, PAG asserted there was no direct infringement and, hence, no induced or contributory infringement.

The Federal Circuit agreed with PAG and held that purchasers of Anton/Bauer’s F plates, indeed, were impliedly licensed to make the patented combination of M and F plates, even when using unpatented M plates obtained from any third parties.

In reaching its decision, the Federal Circuit relied on these factors:

- Anton/Bauer’s F plate sales were unrestricted.

- The F plate has only one use, which is to practice the patented combination.

- The facts “plainly indicate” that a license should be implied, because there was no contrary notice or contractual obligation at the time of sale. The M plates are unpatented. No Anton/Bauer conduct at the sale would have made a customer think it must buy M plates only from Anton/Bauer.

- The F plate sold by Anton/Bauer is a material, not a minor, component of the patented combination.7

Note that the Anton/Bauer decision arguably both narrowed and expanded the Met-Coil rule. In a narrowing sense, the court expressly required the authorized sale item to be a material part of the claimed combination; this materiality requirement may or may not have been integral to the earlier Met-Coil decision, but certainly was not expressly stated there like it was in the Anton/Bauer case. The Anton/Bauer case broadens the Met-Coil rule by extending the rule to patented combinations based on the sale of material, unpatented portions of the combination.8

Additionally, the Anton/Bauer court explained in dicta how the outcome under an implied license theory might have been different if there had been sale restrictions or if the M plate had been patented. This suggests that sale restrictions may appropriately negate an implied license. This also suggests that patenting components of a combination would be sufficient to negate an implied license if a customer were to buy patented components from a third party.9

3. Other Recent Developments in Implied License Law.

Implied licenses can be derived from an express license where the implied license is necessary for the express license to be practiced. Zenith Electronics Corp. v. PDI Communications Systems Inc., 522 F.3d 1348, 86 USPQ2d 1513 (Fed. Cir. 2008).10

Implied licenses cannot be obtained from a licensee who has no authority to confer a right to use. Monsanto Co. v. Scruggs, 459 F.3d 1328, 79 USPQ2d 1813 (Fed. Cir. 2006).

Proof of no non-infringing uses is required when an implied license is derived from an authorized sale but is not required when an implied license is derived from an express license. Zenith Electronics Corp. v. PDI Communications Systems Inc., 522 F.3d 1348, 86 USPQ2d 1513 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

Granting an express license to speakers included an implied license to use the speakers with any compatible television based on the grant language. Zenith Electronics Corp. v. PDI Communications Systems Inc., 522 F.3d 1348, 86 USPQ2d 1513 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

No implied license was found with respect to remote controls based upon speaker sales, because the speakers had non-infringing uses relative to the patented remotes. Zenith Electronics Corp. v. PDI Communications Systems Inc., 522 F.3d 1348, 86 USPQ2d 1513 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

Existence of an implied license and its scope are separate issues. Quanta Computer Inc. v. LG Electronics Inc., 553 US 617, 86 USPQ2d 1673, 1678 (2008); Zenith Electronics Corp. v. PDI Communications Systems Inc., 522 F.3d 1348, 86 USPQ2d 1513 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

A license under a patent as to certain products carries an implied license under narrower or broader continuation patents having the same disclosure absent a clear indication to the contrary in the license. General Protecht Group Inc. v. Leviton Mfg., 651 F.3d 1355, 99 USPQ2d 1275 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

1 See, e.g., Nimmer & Dodd, Modern Licensing Law, §§4:2-4:3 (2007).

2 750 F.2d 903, 925, 223 USPQ 982, 998 (Fed. Cir. 1984).

3 803 F.2d 684, 231 USPQ 474 (Fed. Cir. 1984).

4 Even though the decision refers to the corners as “special,” they were special in terms of their shape but not their patented status.

5 329 F.3d 1343, 66 USPQ2d 1675 (Fed. Cir. 2003).

6 PAG never sold F plates. Thus, any M plate sold by PAG, presumably at a price that was better than M plates sold by Anton/Bauer, was used only in combination with F plates obtained from Anton/Bauer.

7 See footnote 3, 66 USPQ2d at 1680.

8 Met-Coil involved implied licenses under method claims triggered by a sale of equipment used to practice that method.

9 In contrast to the appropriateness of post-sale restrictions in an implied license analysis, post-sale restrictions are quite ineffective at negating exhaustion, a separate legal theory. Also, intent with respect to downstream customers is relevant to implied license, but had not been relevant to exhaustion per Transcore LP v. Electronic Transaction Consultants, 563 F.3d 1271, 90 USPQ2d 1372 (Fed. Cir. 2009). However, the Lifescan decision, discussed above, announced that intent is now relevant to exhaustion.

10 See also Jacobs v. Nintendo of America, Inc., 370 F.3d 1097, 71 USPQ2d 1055 (Fed. Cir. 2004) (the scope of an implied license derived from an express grant clause cannot be construed to render the express grant meaningless, however).