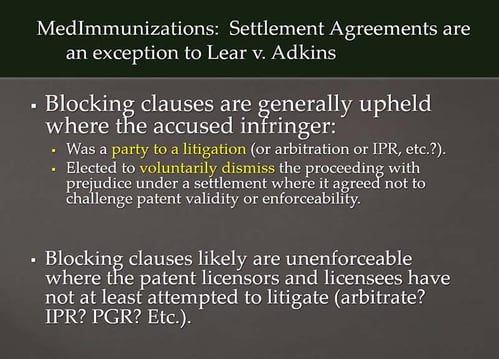

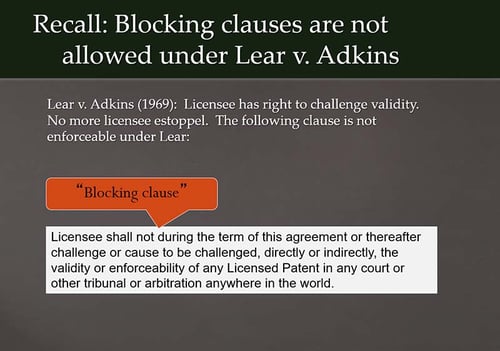

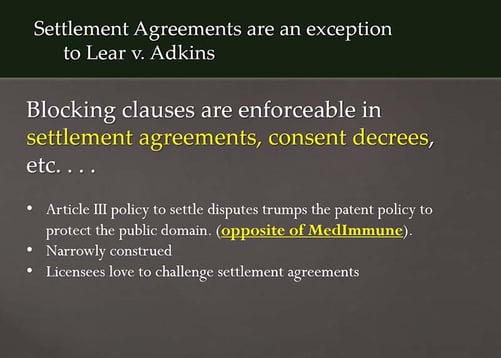

Lear v. Adkins revoked licensee estoppel and authorized licensees to challenge validity. MedImmune extended Lear by allowing validity challenges even if the licensee is not in breach. Generally but not always, license clauses that block validity challenges (“blocking clauses”) are not enforceable under Lear or MedImmune. Settlement agreements are an exception in that blocking clauses are enforceable if incorporated into agreements that settle disputes. This includes consent decrees, licenses, covenants not to sue, and the like.

Lear v. Adkins revoked licensee estoppel and authorized licensees to challenge validity. MedImmune extended Lear by allowing validity challenges even if the licensee is not in breach. Generally but not always, license clauses that block validity challenges (“blocking clauses”) are not enforceable under Lear or MedImmune. Settlement agreements are an exception in that blocking clauses are enforceable if incorporated into agreements that settle disputes. This includes consent decrees, licenses, covenants not to sue, and the like.

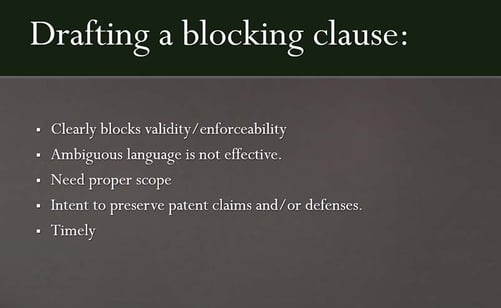

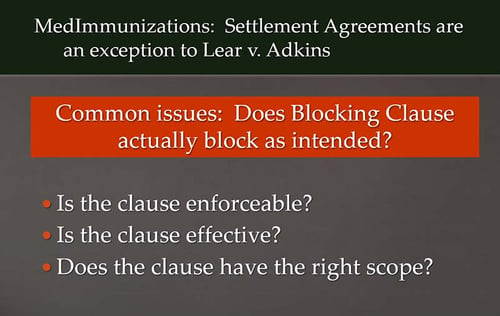

Blocking clauses are enforceable only if the language clearly blocks validity/enforceability attacks. Ambiguous language fails to support blocking. The Federal Circuit demonstrates a bias to construe blocking clauses narrowly. It is also clear that licensees favor challenging settlement agreements. Careful drafting is imperative.

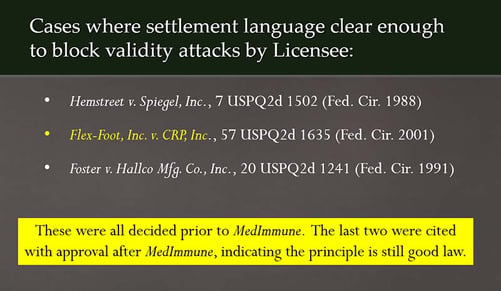

An issue in many cases, therefore, is whether a blocking clause in a settlement agreement actually blocks validity/enforceability challenges as intended. The following are cases where settlement language was clear enough to block validity attacks by the licensee: Hemstreet v. Spiegel, Inc., 7 USPQ2d 1502 (Fed. Cir. 1988); Flex-Foot, Inc. v. CRP, Inc., 57 USPQ2d 1635 (Fed. Cir. 2001); Foster v. Hallco Mfg. Co., Inc., 20 USPQ2d 1241 (Fed. Cir. 1991). These three cases were decided prior to MedImmune. The last two were cited with approval after MedImmune, indicating these cases are still good law.

The following blocking clause is derived from the successful Flex-Foot blocking clause:

The following blocking clause is derived from the successful Flex-Foot blocking clause:

Licensee shall not during the term of this agreement or thereafter challenge or cause to be challenged, directly or indirectly, the validity or enforceability of any Licensed Patent in any court or other tribunal anywhere in the world. Licensee waives any and all invalidity and unenforceability defenses in any future litigation, arbitration, administrative proceeding, mediation, or any other proceeding. This clause shall apply to any product or component thereof, composition or component thereof, or method or portion thereof that is made, used, sold, offered for sale, imported, or otherwise transferred by or for Licensee or any assignees, successors or those who act in concert with any of these parties at any time during the life of the Licensed Patents

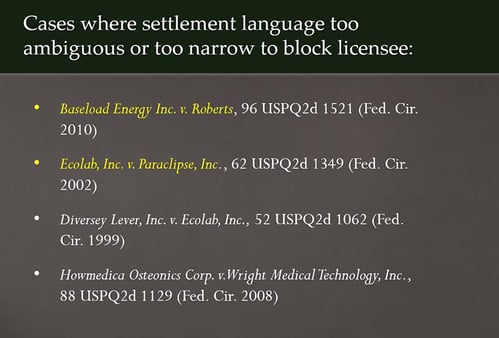

The following are cases where settlement language was too ambiguous or too narrow to block validity attacks: Baseload Energy Inc. v. Roberts, 96 USPQ2d 1521 (Fed. Cir. 2010); Ecolab, Inc. v.Paraclipse, Inc., 62 USPQ2d 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2002); Diversey Lever, Inc. v. Ecolab, Inc., 52 USPQ2d 1062 (Fed. Cir. 1999); Howmedica Osteonics Corp. v. Wright Medical Technology, Inc., 88 USPQ2d 1129 (Fed. Cir. 2008). All of these cases have been cited with approval after MedImmune, indicating their analyses are still good law.

This language failed to block validity attack (Ecolab. v. Paraclipse):

This language failed to block validity attack (Ecolab. v. Paraclipse):

[T]he ‘690 patent is a valid patent.

The following language quite surprisingly failed to block a validity attack (Baseload), because the agreement structure otherwise evidenced an intent not to release patent claims and defenses:

The parties mutually forever release and discharge the other parties . . . From ANY AND ALL losses, liabilities, claims, expenses, demands, and causes of action of EVERY KIND AND NATURE, known and unknown, suspected or unsuspected, disclosed or undisclosed, fixed or contingent, whether direct or indirectly that the parties ever had, now have, or hereafter may have or be able to assert against the other parties . . .

In summary, blocking clauses must be carefully drafted to be effective and there are many counter-intuitive pitfalls. But there are many cases to guide drafting efforts. Flex-Foot, in particular, offers a helping hand and provides an excellent, litigation-tested clause that worked.