The Government is inhuman. I’m not paranoid. The Supreme Court says so.

Return Mail, Inc. v. Postal Service, 139 S. Ct. 1853 (2019)

Is a federal agency such as the U.S. Postal Service a person? And what does this have to do with license practice? It turns out, plenty.

Return Mail patented a method to process undeliverable mail. After the United States Postal Service (USPS), a federal agency, introduced a service that processed undeliverable mail, Return Mail sued the USPS for patent infringement under a patent including business method claims. The USPS countered by filing a post grant CBM (covered business method) review of the patent and succeeded in invalidating the patent claims. Section 101 issues dominated the CBM proceeding, and the business method claims were determined to be ineligible for patent protection. The Federal Circuit affirmed. The asserted patent appeared to be dead.

Return Mail patented a method to process undeliverable mail. After the United States Postal Service (USPS), a federal agency, introduced a service that processed undeliverable mail, Return Mail sued the USPS for patent infringement under a patent including business method claims. The USPS countered by filing a post grant CBM (covered business method) review of the patent and succeeded in invalidating the patent claims. Section 101 issues dominated the CBM proceeding, and the business method claims were determined to be ineligible for patent protection. The Federal Circuit affirmed. The asserted patent appeared to be dead.

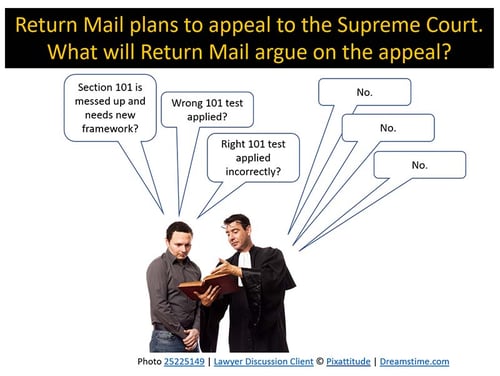

Undaunted, Return Mail sought Supreme Court review. Since Section 101 (patent eligibility) issues dominated in the CBM proceeding, would it not be most likely that Return Mail would seek Supreme Court review on those Section 101 issues? Commentators widely criticize Section 101 jurisprudence as a mess that needs fixing, so an appeal based on Section 101 seemed likely.

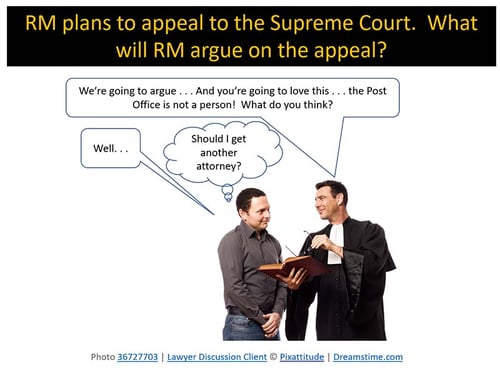

As it turned out, the main issue on appeal was nothing what you would expect. Instead of seeking Supreme Court review on one of the scholarly, expected challenges to Section 101, Return Mail asked the Supreme Court to consider whether the USPS or any other federal agency is a person. At first blush, this might not appear to be an issue worthy of Supreme Court attention, but the Supreme Court took the appeal. The statutes that authorize post grant review proceedings only allow a statutory “person” to bring these actions. Any entity that is not a statutory “person” has no standing to bring a CBM or any other post grand proceeding.

As it turned out, the main issue on appeal was nothing what you would expect. Instead of seeking Supreme Court review on one of the scholarly, expected challenges to Section 101, Return Mail asked the Supreme Court to consider whether the USPS or any other federal agency is a person. At first blush, this might not appear to be an issue worthy of Supreme Court attention, but the Supreme Court took the appeal. The statutes that authorize post grant review proceedings only allow a statutory “person” to bring these actions. Any entity that is not a statutory “person” has no standing to bring a CBM or any other post grand proceeding.

The post grant statutes used “person” without ever defining the term. In the absence of a statutory definition, does “person” include a federal agency such as the USPS?

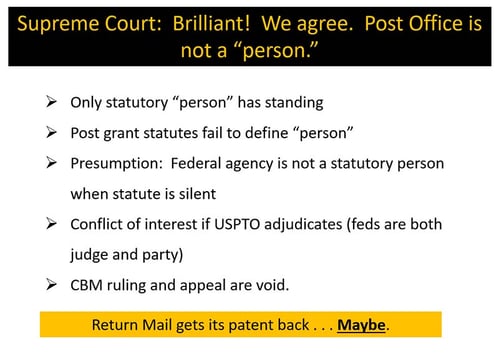

The Supreme Court determined that the USPS and other federal agency are not “persons” under the post grant review statutes. Hence, the USPS had no standing to bring the CBM action. The USPTO and Federal Circuit determinations of invalidity of the Return Mail patent under Section 101 were reversed. The patent remained valid.

The Supreme Court relied on a couple of factors to determine that the USPS is not a “person” under the post grant review statutes. Case law precedent indicates a presumption that a federal agency is not a “person” when the statute offers no definition. The Supreme Court also perceived a conflict of interest where the USPTO (a federal agency) adjudicated a dispute with another federal agency as a party. This would be like the other side’s lawyer also being the judge. Ironically, perhaps, the Court did not perceive a similar conflict in the present case where the federal judiciary is asked to adjudicate disputes with another federal agency as a party. Somehow, the legislative tribunal in the USPTO is vulnerable to being tainted by such a conflict, but not the federal judiciary.

The Supreme Court relied on a couple of factors to determine that the USPS is not a “person” under the post grant review statutes. Case law precedent indicates a presumption that a federal agency is not a “person” when the statute offers no definition. The Supreme Court also perceived a conflict of interest where the USPTO (a federal agency) adjudicated a dispute with another federal agency as a party. This would be like the other side’s lawyer also being the judge. Ironically, perhaps, the Court did not perceive a similar conflict in the present case where the federal judiciary is asked to adjudicate disputes with another federal agency as a party. Somehow, the legislative tribunal in the USPTO is vulnerable to being tainted by such a conflict, but not the federal judiciary.

What is the lesson for license practice? Statistics show that patent challengers still have an advantage in post grant proceedings. In other words, post grant proceedings favor patent challengers in view of statistics. This means that post grant proceedings are a potent tool for patent challengers, but a bane for patent owners. Because federal agencies are denied access to post grant proceedings as petitioners as a result of Return Mail, patents are somewhat stronger in terms of validity against federal agencies than against “persons.” In effect, federal agencies are denied access to potent weapons used to invalidate patents. This increases the probabilities of doing economically reasonable license deals with federal agencies, as the agencies can only attack patents now in ex parte reexamination or federal court.

Possibly, the post grant statutes could be amended so that “person” encompasses federal agencies. Perhaps no such amendment will be seen, as this would not resolve the conflict of interest perceived by the Supreme Court. For now, unless and until the law is changed, federal agencies may be more willing to consider economically reasonable deals to avoid the expense and possible outcomes of claims court battles.