Who wears the boxing gloves?

Alexsam, Inc. v. Mastercard, Inc., No. 1:2015cv02799 (E.D.N.Y. 2019)

Litigating parties can be surprisingly creative in creating and defending against causes of action in license disputes. No matter how straightforward the issues appear to be from your own perspective, the other party will have a different perspective of the issues. You must wear the shoes of both parties to optimize your own moves and to predict the moves of the other party.

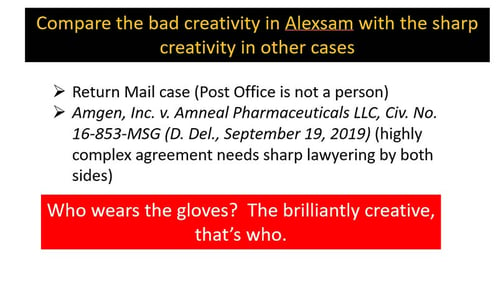

License parties in disputes can display surprising creativity . . . but not always in a good way (a.k.a, What the heck were you thinking when you came up with this litigation strategy?). Sometimes, creative application of law and fact shines with brilliance. Other times, not so much.

License parties in disputes can display surprising creativity . . . but not always in a good way (a.k.a, What the heck were you thinking when you came up with this litigation strategy?). Sometimes, creative application of law and fact shines with brilliance. Other times, not so much.

Alexsam is a “not so much” example where a desperate licensor advanced an agreement construction that, even being polite, was foolish and doomed. Yet, licensor stuck with the argument all the way through trial, which licensor lost soundly. One can speculate that licensor’s initial litigation strategy might have been mainly a strong expectation that the accused infringer would surely settle somewhere in the discovery phase and that a trial would never happen. But, trials happen. Not all cases settle. While it is reasonable to speculate that your own dispute might settle inasmuch as most cases do in fact settle before trial, this kind of expectation cannot be the foundation of your litigation strategy. In contrast to what the plaintiff-licensor appears to have done in Alexsam, heading into litigation with an excellent strategy well-grounded in fact and law is paramount, particularly when you are plaintiff as Alexsam was here!

In Alexsam, the patent owner Alexsam licensed patent rights to Mastercard. The license grant authorized Mastercard to practice card transactions “covered by” one of the licensed patents. Mastercard agreed to pay a royalty for each card transaction “covered by” the licensed patents.

Mastercard did not pay royalty on a large volume of card transactions on grounds that no patent claim of the licensed patents covered the transactions. Accordingly, no royalty contractually was due under the license, and there was no infringement.

It does not appear from the court’s opinion that Alexsam challenged that its patent claims covered any of the card transactions at issue. It appears that Alexsam conceded to non-infringement. Was there anything in the license that might have caused Mastercard to have a contract obligation to pay royalty on the accused transactions anyway?

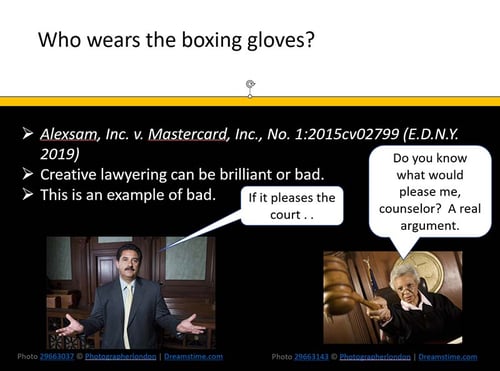

The licensor desperately wanted to capture royalty for the Mastercard card transactions outside its claim scope, yet somehow within the scope of the license anyway. Licensor did in fact cook up an agreement construction to serve its desperate objective. Although arguably a creative concoction, it was not the brilliant kind. It was the other kind. Licensor argued that the terminology “covered by” in the license grant and royalty clauses was ambiguous so that “covered by” meant both subject matter that infringes a patent claim as well as subject matter that does not infringe any patent claim. The practical effect is that licensor argued that “covered by” meant both “covered by” and “not covered by.”

The licensor desperately wanted to capture royalty for the Mastercard card transactions outside its claim scope, yet somehow within the scope of the license anyway. Licensor did in fact cook up an agreement construction to serve its desperate objective. Although arguably a creative concoction, it was not the brilliant kind. It was the other kind. Licensor argued that the terminology “covered by” in the license grant and royalty clauses was ambiguous so that “covered by” meant both subject matter that infringes a patent claim as well as subject matter that does not infringe any patent claim. The practical effect is that licensor argued that “covered by” meant both “covered by” and “not covered by.”

The court had no trouble rejecting the proposed construction. In contrast to the licensor proposal, the court explained that the language “covered by” has a straightforward meaning in the patent world, and licensor presented no other precedent or other evidence that a different meaning should prevail. Licensor exited trial with its royalty pockets empty.

Certainly, when a patent license collects royalty under patent rights, there is always a risk that licensee will design around the patent claims, invalidate the patent claims, or otherwise attempt to avoid its royalty obligation. Mastercard implemented a successful design around here. What could Alexsam or any other patent licensor have done differently?

Many strategies are available. Here are a few. Alexsam could have used the power of know how. If Alexsam had licensed both patent rights and know how, it is less likely that Mastercard could have avoided both the patent rights and the know how rights. Perhaps Mastercard could have collected more of its royalty up front as an initial fee so that less royalty would be at risk. If its bargaining power allowed, it could have contracted to receive a minimum royalty each year to keep the license in force and have charged an early exit fee if Mastercard chose to terminate early. With a pending application in the family, and if supported by the written description, Alexsam could have tuned its claim coverage to keep Mastercard in the license. Alexsam could have kept up with research and development, creating new commercially desirable patent rights or new know how to incorporate into the license via amendment. If there were confidentiality obligations in the license, Alexsam could have investigated whether any of the Mastercard design arounds were improperly developed from Alexsam Confidential Information in violation of confidentiality or use restrictions.

The Alexsam license likely had another problem. Alexsam sought production of documents relating to the license, but Mastercard refused to provide these. Apparently, nothing in the agreement required that such documents be disclosed as a matter of a contract obligation, as the opinion did not mention the contract as a basis to authorize or refuse the discovery request. This suggests that the audit clause in the Alexsam license might have been deficient, as document access most likely would have been handled there.

Audit clauses are glossed over too often. They might seem to be merely background boilerplate at the time of drafting and negotiation. But audit clauses are very useful and powerful tools in license disputes that could erupt down the road. The audit clause in Alexsam easily could have been written to encompass access to the kinds of documents that Alexsam sought through discovery. Mastercard would have had to produce these as a matter of contract obligation. Alexsam and any other patent licensor can benefit from a powerful, well-crafted audit clause.

Audit clauses are glossed over too often. They might seem to be merely background boilerplate at the time of drafting and negotiation. But audit clauses are very useful and powerful tools in license disputes that could erupt down the road. The audit clause in Alexsam easily could have been written to encompass access to the kinds of documents that Alexsam sought through discovery. Mastercard would have had to produce these as a matter of contract obligation. Alexsam and any other patent licensor can benefit from a powerful, well-crafted audit clause.

Crazy did not work for the licensor in Alexsam. Sometimes, though, crazy works. Recall our discussion of the Return Mail case above. There, Section 101 confounded the patent owner, who initially lost its patent rights as being patent ineligible. Rather than pursue Federal Circuit and then Supreme Court review on re-thinking Section 101, which would be a mainstream approach, patent owner creatively propounded the theory that a federal agency such as the U.S. postal service is not a statutory person. Not being a statutory person, the federal agency has no standing to initiate post grant CBM review of the patent rights.

Put yourself into the shoes of the client in the very first meeting with counsel where this “person” theory is proposed. Maybe, as that client, you were expecting a brash and brilliant 101 argument rather than a theory as to who is a person and who is not. Initially, as the client, might you be nervous thinking your whole appeal is based on a “person” hanging by such a thin thread? Would you be reviewing your contact list for other counsel perhaps?

Regardless of what those initial impressions might have been, counsel and client courageously forged ahead with this “person” theory. They stepped into the first ring with the District Court as referee and got knocked down soundly. They staggered into the second ring with the Federal Circuit as referee and again got knocked down soundly on that first appeal. Getting knocked down twice by two different tribunals is close to a complete knock-out. Both the district court and the Federal Circuit indicated that the “person” theory had no punch or legs of its own.

Did this team concede and go home to battle a different fight on a different day? No, they kept fighting, taking their “person” theory up another level of judicial review to the Supreme Court, where ultimately they emerged triumphant. This was Rocky beating Apollo Creed in the final bout.

Who wears the boxing gloves in a license? Litigants who are creative in the good way, that’s who.